Chief: Research & Development

Professional Communications, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

Does management differ between municipalities and corporations? Municipalities are more tightly bound by legislative mandates. In addition, cities tend to be more unionized. Labor contracts more explicitly define what can and cannot be done. These factors are enough to throw up some flags. But there is more.

Municipalities are much closer to their client base than are their corporate brethren. City employees are likely to meet their constituents on the street or even live next to them. They are subject to daily scrutiny by blogs, newspapers, radio and television stations. Few corporations contend with this kind of transparency. And there is still more.

Up until recently jobs in the municipal sector have been viewed as more secure than their corporate counterpart. The popular perception is that this causes cities to attract people who value security over opportunity. If this is true it is likely to affect the kind of management that can and should be done.

This evidence-based research tests the direction and degree of the actual differences in city and corporate management. A video that examines the city executive element of this research in some detail is available on Youtube. Simply click the icon on the right to link to it.

THE SAMPLE

This study was drawn from 19 cities in 10 states. The cities ranged in size from 824 to 751,000 people. The average size was 128,900 and have a median (i.e., midpoint) of 73,900. The city data were the “I Opt” scores for 175 executives and 72 supervisors.

The corporate sample consisted of 5,476 people (executives and supervisors) for whom titles were known drawn from about 1,000 “for profit” firms. International locations are represented but the largest portion of this sample is United States based.

Management divides into two categories. Executives have distinct groups reporting to them or they head a distinct organizational function. Supervisors lead a particular group within a function.

The research base is not a random sample. But is large enough to be considered strongly indicative. The division of people by rank is believed to be reasonable in terms of the purposes of this study.

EXECUTIVE MANAGEMENT

“I Opt” scores for 175 city executives were compared to 4,963 corporate executives. “I Opt” scores translate directly into behaviors that affect management. A sampling of the behaviors predicted by “IOpt” strategic styles and patterns is shown in Table1.

Table 1

SAMPLE OF "I OPT" BEHAVIORAL CHARACTERISTICS

SAMPLE OF "I OPT" BEHAVIORAL CHARACTERISTICS

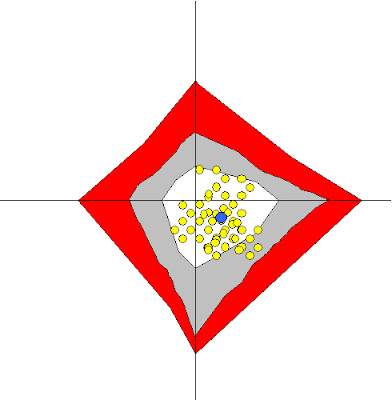

The average “I Opt” scores of city and corporate executives were compared. Differences were tested for statistical significance. The results are shown in Graphic 1.

Graphic 1

COMPARISON OF CITY AND CORPORATE EXECUTIVES

COMPARISON OF CITY AND CORPORATE EXECUTIVES

Graphic 1 shows that city and corporate executives are virtually identical in their decision making approach. Tests of significance confirm that both cities and firms have the same kind of people in their executive ranks. An “average” executive from either group can move to the other and—in terms of their approach to decision making—they would be indistinguishable.

Averages can hide as much as they disclose. Graphic 2 compares the proportion of city and corporate executives in three strength categories—high, moderate and low. For example, 20% of city and 15% of the corporate executives might score “high” in a style. The chart would show city employees with 33% more “high level” commitment in that style (i.e., <20%-15%= 15=" 33.3%">).

Graphic 2

CITY AND CORPORATE EXECUTIVES

"I OPT" STRATEGIC STYLE COMMITMENT

The differences in the action categories of Logical Processor (methodical action) and Reactive Stimulator (spontaneous action) are statistically insignificant. The differences could be just random variations around a common standard. Both city and corporate executives are distributed roughly equally among the three categories of strength in these action-oriented categories.

The analytical Hypothetical Analyzer (analysis, assessment, evaluation) is another story. There are more city workers with “high” levels of HA. A z-Ratio test of proportional significance shows that this difference is not a random variation. This means that if we were to take repeated samples, cities are likely to continue to have more executives in the “high” category than would corporations.

City executives also tend to clump more in the “high” category of the idea oriented Relational Innovator style (ideas, options, alternatives). The statistic just misses the academic standard (6% versus the 5% standard). However, chances are still 94 times out of 100 that the result would be the same if the sample were retaken. This is probably a real difference and is accepted as marginally significant.

The HA (analysis) and RI (ideas) are thought based strategies. The RI generates ideas and the HA analyzes them. Cities appear to attract and retain executives with high levels of this capacity. On the whole, city executives are “thinkers.”

There is another aspect of the style profile worth noting. Cities also have more people clustered at “low “ levels in these capacities (HA and RI) than do their corporate peers. Executives at opposite poles will tend to view decisions differently. For example, a person high in HA may want time to study while another low in HA could prefer to act quickly. This creates a natural source of tension as competing ideas and contesting views on the "right" way to analyze them work themselves out.

Corporate executives do not have to contend with this divergence. Their executives tend to cluster at “moderate” level of commitment. There is just less distance to bridge. This makes it easier for corporate executives to arrive at a common position. It is reasonable to expect that cities face a bigger coordination challenge among their executives than do corporations. In other words, corporations are likely to have an easier time at internal executive coordination than will their city peers.

SUPERVISORY MANAGEMENT

City supervisors differ markedly from their executive colleagues. A total of 72 city and 513 corporate supervisors were contrasted. Graphic 3 shows the results.

City supervisors put most emphasis on the Logical Processor (methodical action) strategy. They exceed their corporate peers by about 14%. This is likely to manifest itself in behaviors such as greater risk avoidance, more rigidity and higher detail sensitivity. The probable behaviors also include greater precision, heightened dependability and more determination. No style is all good or bad.

The high LP commitment has a corollary. The idea oriented RI style falls about 13% short of their corporate equals. This means city supervisors are less likely to offer totally new options, engage in freewheeling idea sessions or be as tolerant of dissent.

The difference in supervisor styles are strong enough noticeable. In addition, the style differences are statistically significant. It is probable that these differences are “real” and will be “seen” in city management.

Overall, city supervisors will reinforce the popular conception of city employees. They are likely to be measured in their response, follow rules closely and be less than empathetic. Their constituents are likely to notice these qualities. The fact that they will also be reliable, stable and committed will be less visible.

OVERALL PICTURE OF CITY MANAGEMENT

City executives are likely to have more ideas than their corporate counterparts. That means more ideas competing for approval. A minority of city executives with a low inclination toward idea generation may restrain this idea overabundance. But they are unlikely to prevail. More likely, the competing ideas will have to “fight it out” for dominance. In the process, tension is likely to be generated in excess of that produced in corporations.

As matters progress, another factor comes into play—analysis. City executives appear to be over-endowed with this capacity. What this means is that the high volume of ideas will likely be subject to the full spectrum analytical options. During this stage it is likely that different analyses will compete for depth of understanding. In other words, a game of analytical “one-upsmanship” is likely to evolve. This is likely to extend far beyond that experienced in corporations. Analysis is not free. The relative cost of city decisions is likely to outpace the cost of a similar corporate decision.

And it is still not done. As proposals move from ideas to implemented programs, there is still another hurdle. City supervisors are proportionately stronger in the disciplined Logical Processor (LP) style than their corporate brethren. This is a demanding approach. The goal is “do it right, the first time and every time.” The preparation needed to satisfy this goal is also not free. Costs in terms of time and money can reasonably be expected to exceed similar programs implemented in corporations.

Is the above scenario a bad thing? Not necessarily. On important decisions that seriously affect the well-being of the cities constituencies, it could be optimal. The problem is that this is a structural condition. It will happen on even minor or even inconsequential matters. In these latter cases, city resources are being wasted.

Overall, it appears that corporations do have a structural edge. This is not because the cities lack any strategic style capability. In fact, it is just the opposite. They appear to be over-endowed with capacities in idea generation, analysis and precise execution. This extra horsepower carries with it extra costs. This includes tension in the idea phase and both time and cost penalties in the analytical and implementation phases.

Counter-intuitively, the penalties paid by cities are not due to any “weakness.” They are due to strengths. The good thing about this condition is that correcting it is only a matter of focusing and directing strength already present. This is much easier and cheaper than acquiring absent capacities from the outside.

IMPROVING CITY EXECUTIVE DECISION MAKING

The issues identified in this research are likely to resonate within the administration of many cities. There is a generic approach that is likely to help in a material way. It rests on the fact that everyone has an information processing preference. It cannot be avoided. No one can pay attention to everything around them all of the time. We all pay attention to some things and ignore others. As we do this we develop a "typical" method of processing information. This is an "I Opt" strategic style. It is what others see and react to.

An instrument that identifies strategic styles in a non-threatening, non-invasive and work-related manner will improve city functioning. The “I Opt” individual report serves that function. People can use it to share their preferences with others. Since every perspective is valid, this helps the people involved adjust their communication with each other. Transactions are smoothed.

The reason is simple. It is in everyone’s interest. A person seeking to convince another to adopt their position stands a better chance if they speak in a manner preferred by the person being convinced. The person on the receiving end gets the information in a way that they can evaluate without having to “translate” it. The more people that adopt this strategy, the smoother will be the decision transactions in which they are all engaged. No mystery, just common sense.

The general strategy outlined above has been demonstrated effective over many years. However, it has limits. It is individually oriented. The decisions in cities are group based efforts. The specific mix of people in the group matters. Improving this aspect of city governance requires tools able to assess a group as a group. In other words, ALL of the people involved interacting SIMULTANEOUSLY. And any particular mix of people may not fully reflect the national profile outlined in this research.

Further advancing city improvement requires an assessment each particular group within city government. That assessment must be quick, inexpensive and accurate. The result should be a diagnostic uniquely targeted to the specific conditions within that group. In addition, specific actions needed to remedy that group’s vulnerabilities should be specified. The “I Opt” TeamAnalysis™ satisfies these conditions. Generic team building processes may help. But they cannot match the tailored interventions provided by “I Opt” technology.

IMPROVING CITY EXECUTIVE-SUPERVISORY MANAGEMENT

If supervisory management is included in the interventions outlined above, many of the issues involved in the relation of executives to supervisors will have been resolved. But it is likely that some will remain. Again, the issue is the strength of commitment rather than the absence of a particular quality.

The supervisory levels are characterized by a virtual unanimous subscription to the Logical Processor (methodical action) strategic style. The result is a natural dichotomy of perspective between executives and supervisors.

Executives tend to value thought, integrity, creativity and compelling logic. The supervisory elements are in pursuit of perfection in execution. They tend to value and expect explicit “how to” specification. They also need time to hone a new direction to a point where they are absolutely sure it works. Finally, they need to see how the new course “fits in” with all of the other things they have to do. When these conditions are met they are able to execute a course of action with precision.

City supervisors will probably view the executive’s efforts as a half-baked effort. For them, the job is done when detailed, step-by-step procedures are in place and fully tested. Executives are likely to believe the job done when plans have been laid, approvals received and responsibilities delegated. A likely outcome of executive-supervisory relations is tension. One party sees the job as done—only execution remains. The other sees a giant gap that remains unfilled.

Viewed in this manner it is obvious that nether city executives or supervisors are “right” or “wrong.” The issue lies in the interface between the two groups. And the gap between the groups is broader than that experienced in corporations. In corporations the groups are distinct but closer together.

Again, identifying the differences in decision making processes will help inform both parties as to exactly what is “going on” between them. Here, a little more effort devoted to why the processes favored by executives and supervisors are both necessary to effective city functioning is probably warranted. The LP style favored by the supervisors is naturally skeptical and will probably require some additional effort to actually “take.” However, once it does a new level of understanding is gained. Experience in applying “I Opt” technology almost invariably creates an insight that automatically improves tolerance for different views. This outcome alone is enough to improve the functioning and productivity of city government.

Further gains are available by helping executives adjust the nature and way their direction is given. The natural tendency will be for executives to follow the “golden rule.” It they do, they are likely to miss the mark. A better alignment of the direction to the needs of the people getting those directions can go far. This is a simple but not an obvious process. A bit of outside counsel explaining what needs to be done, why it is needed and how to go about it is all that is usually required.

SUMMARY

Cities face a managerial challenge. It exists within the executive ranks and between the executive and supervisory ranks. The difficulty is founded in strength, not weakness. The strength of all parties can make the relationship between functions and levels a challenge.

The challenge cities face is greater than their corporate counterparts. This translates to more opportunity. Improving things by 25% means more when that 25% is multiplied by a big number than a small one. This means that it is wise for cities to invest in organizational interventions to a greater extent than do their corporate kin. This is common sense, it is not rocket science.

“I Opt” technology is designed to be accessible to everyone. However, city executives and supervisors have much to do. Spending time personally assessing the implications of their strategies is bound to be low on the “to do” list. Providing them help in condensing, digesting and implementing effective improvement strategies would seem to be a smart. A small investment can yield high and continuing dividends.

The benefit for the organizational intervention strategies will accrue to all involved. Things get done faster and at less expense. City workers get a more hospitable, effective and efficient environment. Citizens would see a workforce more attuned to their needs. The investment in improving organizational functioning is small. Yet it could be one of the most effective tools available for helping cities meet the challenges of difficult economic times.

CITY AND CORPORATE EXECUTIVES

"I OPT" STRATEGIC STYLE COMMITMENT

The differences in the action categories of Logical Processor

The analytical Hypothetical Analyzer

City executives also tend to clump more in the “high” category of the idea oriented Relational Innovator

The HA (analysis) and RI (ideas) are thought based strategies. The RI generates ideas and the HA analyzes them. Cities appear to attract and retain executives with high levels of this capacity. On the whole, city executives are “thinkers.”

There is another aspect of the style profile worth noting. Cities also have more people clustered at “low “ levels in these capacities (HA and RI) than do their corporate peers. Executives at opposite poles will tend to view decisions differently. For example, a person high in HA may want time to study while another low in HA could prefer to act quickly. This creates a natural source of tension as competing ideas and contesting views on the "right" way to analyze them work themselves out.

Corporate executives do not have to contend with this divergence. Their executives tend to cluster at “moderate” level of commitment. There is just less distance to bridge. This makes it easier for corporate executives to arrive at a common position. It is reasonable to expect that cities face a bigger coordination challenge among their executives than do corporations. In other words, corporations are likely to have an easier time at internal executive coordination than will their city peers.

City supervisors differ markedly from their executive colleagues. A total of 72 city and 513 corporate supervisors were contrasted. Graphic 3 shows the results.

Graphic 3

COMPARISON OF CITY AND CORPORATE SUPERVISORS

COMPARISON OF CITY AND CORPORATE SUPERVISORS

City supervisors put most emphasis on the Logical Processor (methodical action) strategy. They exceed their corporate peers by about 14%. This is likely to manifest itself in behaviors such as greater risk avoidance, more rigidity and higher detail sensitivity. The probable behaviors also include greater precision, heightened dependability and more determination. No style is all good or bad.

The high LP commitment has a corollary. The idea oriented RI style falls about 13% short of their corporate equals. This means city supervisors are less likely to offer totally new options, engage in freewheeling idea sessions or be as tolerant of dissent.

The difference in supervisor styles are strong enough noticeable. In addition, the style differences are statistically significant. It is probable that these differences are “real” and will be “seen” in city management.

Overall, city supervisors will reinforce the popular conception of city employees. They are likely to be measured in their response, follow rules closely and be less than empathetic. Their constituents are likely to notice these qualities. The fact that they will also be reliable, stable and committed will be less visible.

OVERALL PICTURE OF CITY MANAGEMENT

City executives are likely to have more ideas than their corporate counterparts. That means more ideas competing for approval. A minority of city executives with a low inclination toward idea generation may restrain this idea overabundance. But they are unlikely to prevail. More likely, the competing ideas will have to “fight it out” for dominance. In the process, tension is likely to be generated in excess of that produced in corporations.

As matters progress, another factor comes into play—analysis. City executives appear to be over-endowed with this capacity. What this means is that the high volume of ideas will likely be subject to the full spectrum analytical options. During this stage it is likely that different analyses will compete for depth of understanding. In other words, a game of analytical “one-upsmanship” is likely to evolve. This is likely to extend far beyond that experienced in corporations. Analysis is not free. The relative cost of city decisions is likely to outpace the cost of a similar corporate decision.

And it is still not done. As proposals move from ideas to implemented programs, there is still another hurdle. City supervisors are proportionately stronger in the disciplined Logical Processor (LP) style than their corporate brethren. This is a demanding approach. The goal is “do it right, the first time and every time.” The preparation needed to satisfy this goal is also not free. Costs in terms of time and money can reasonably be expected to exceed similar programs implemented in corporations.

Is the above scenario a bad thing? Not necessarily. On important decisions that seriously affect the well-being of the cities constituencies, it could be optimal. The problem is that this is a structural condition. It will happen on even minor or even inconsequential matters. In these latter cases, city resources are being wasted.

Overall, it appears that corporations do have a structural edge. This is not because the cities lack any strategic style capability. In fact, it is just the opposite. They appear to be over-endowed with capacities in idea generation, analysis and precise execution. This extra horsepower carries with it extra costs. This includes tension in the idea phase and both time and cost penalties in the analytical and implementation phases.

Counter-intuitively, the penalties paid by cities are not due to any “weakness.” They are due to strengths. The good thing about this condition is that correcting it is only a matter of focusing and directing strength already present. This is much easier and cheaper than acquiring absent capacities from the outside.

IMPROVING CITY EXECUTIVE DECISION MAKING

The issues identified in this research are likely to resonate within the administration of many cities. There is a generic approach that is likely to help in a material way. It rests on the fact that everyone has an information processing preference. It cannot be avoided. No one can pay attention to everything around them all of the time. We all pay attention to some things and ignore others. As we do this we develop a "typical" method of processing information. This is an "I Opt" strategic style. It is what others see and react to.

An instrument that identifies strategic styles in a non-threatening, non-invasive and work-related manner will improve city functioning. The “I Opt” individual report serves that function. People can use it to share their preferences with others. Since every perspective is valid, this helps the people involved adjust their communication with each other. Transactions are smoothed.

The reason is simple. It is in everyone’s interest. A person seeking to convince another to adopt their position stands a better chance if they speak in a manner preferred by the person being convinced. The person on the receiving end gets the information in a way that they can evaluate without having to “translate” it. The more people that adopt this strategy, the smoother will be the decision transactions in which they are all engaged. No mystery, just common sense.

The general strategy outlined above has been demonstrated effective over many years. However, it has limits. It is individually oriented. The decisions in cities are group based efforts. The specific mix of people in the group matters. Improving this aspect of city governance requires tools able to assess a group as a group. In other words, ALL of the people involved interacting SIMULTANEOUSLY. And any particular mix of people may not fully reflect the national profile outlined in this research.

Further advancing city improvement requires an assessment each particular group within city government. That assessment must be quick, inexpensive and accurate. The result should be a diagnostic uniquely targeted to the specific conditions within that group. In addition, specific actions needed to remedy that group’s vulnerabilities should be specified. The “I Opt” TeamAnalysis™ satisfies these conditions. Generic team building processes may help. But they cannot match the tailored interventions provided by “I Opt” technology.

IMPROVING CITY EXECUTIVE-SUPERVISORY MANAGEMENT

If supervisory management is included in the interventions outlined above, many of the issues involved in the relation of executives to supervisors will have been resolved. But it is likely that some will remain. Again, the issue is the strength of commitment rather than the absence of a particular quality.

The supervisory levels are characterized by a virtual unanimous subscription to the Logical Processor (methodical action) strategic style. The result is a natural dichotomy of perspective between executives and supervisors.

Executives tend to value thought, integrity, creativity and compelling logic. The supervisory elements are in pursuit of perfection in execution. They tend to value and expect explicit “how to” specification. They also need time to hone a new direction to a point where they are absolutely sure it works. Finally, they need to see how the new course “fits in” with all of the other things they have to do. When these conditions are met they are able to execute a course of action with precision.

City supervisors will probably view the executive’s efforts as a half-baked effort. For them, the job is done when detailed, step-by-step procedures are in place and fully tested. Executives are likely to believe the job done when plans have been laid, approvals received and responsibilities delegated. A likely outcome of executive-supervisory relations is tension. One party sees the job as done—only execution remains. The other sees a giant gap that remains unfilled.

Viewed in this manner it is obvious that nether city executives or supervisors are “right” or “wrong.” The issue lies in the interface between the two groups. And the gap between the groups is broader than that experienced in corporations. In corporations the groups are distinct but closer together.

Again, identifying the differences in decision making processes will help inform both parties as to exactly what is “going on” between them. Here, a little more effort devoted to why the processes favored by executives and supervisors are both necessary to effective city functioning is probably warranted. The LP style favored by the supervisors is naturally skeptical and will probably require some additional effort to actually “take.” However, once it does a new level of understanding is gained. Experience in applying “I Opt” technology almost invariably creates an insight that automatically improves tolerance for different views. This outcome alone is enough to improve the functioning and productivity of city government.

Further gains are available by helping executives adjust the nature and way their direction is given. The natural tendency will be for executives to follow the “golden rule.” It they do, they are likely to miss the mark. A better alignment of the direction to the needs of the people getting those directions can go far. This is a simple but not an obvious process. A bit of outside counsel explaining what needs to be done, why it is needed and how to go about it is all that is usually required.

SUMMARY

Cities face a managerial challenge. It exists within the executive ranks and between the executive and supervisory ranks. The difficulty is founded in strength, not weakness. The strength of all parties can make the relationship between functions and levels a challenge.

The challenge cities face is greater than their corporate counterparts. This translates to more opportunity. Improving things by 25% means more when that 25% is multiplied by a big number than a small one. This means that it is wise for cities to invest in organizational interventions to a greater extent than do their corporate kin. This is common sense, it is not rocket science.

“I Opt” technology is designed to be accessible to everyone. However, city executives and supervisors have much to do. Spending time personally assessing the implications of their strategies is bound to be low on the “to do” list. Providing them help in condensing, digesting and implementing effective improvement strategies would seem to be a smart. A small investment can yield high and continuing dividends.

The benefit for the organizational intervention strategies will accrue to all involved. Things get done faster and at less expense. City workers get a more hospitable, effective and efficient environment. Citizens would see a workforce more attuned to their needs. The investment in improving organizational functioning is small. Yet it could be one of the most effective tools available for helping cities meet the challenges of difficult economic times.