Chief: Research & Development

Professional Communications, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

This research blog investigates whether students attending Second Career and traditional Master of Science programs are equal sources of nurse management talent. The research finds that program participants are different and will appear so to observers. But they are virtually identical in their ability to provide “management ready” talent.

The research then compares nursing with people pursuing a master’s degree in other professions. It finds that nursing MS programs provide less than half as much managerial perspective to the talent pool than do other professions.

Finally, a Migration Strategy of offsetting the shortage of nursing is offered. The strategy can be applied to any nurse (AA, BS or MS) and provides a non-threatening, measured option for both the nurse and the medical institution. This strategy is more fully specified in an Addendum to this research blog.

DIFFERENT KINDS OF MS GRADUATES

There are two major programs producing nurses with MS degrees. The traditional program admits nurses who have completed undergraduate nursing programs. The Second Career MS program admits students with who completed their undergraduate degree in other fields.

Data is available from 29 students completing Second Career Master of Science (MS) degrees and 81 students in a traditional MS program at a major research university. Graphic 1 shows that the students in the two programs are statistically different along two dimensions.

Graphic 1

SECOND CAREER AND TRADITIONAL

MASTER OF SCIENCE PROGRAMS

SECOND CAREER AND TRADITIONAL

MASTER OF SCIENCE PROGRAMS

Traditional students put more reliance on the idea-oriented RI strategy. The Second Career students put greater emphasis on the disciplined action of the LP style. However, this is not the relevant test for the issue at hand. That issue is how well the two group profiles match the needs of nursing management.

Graphic 2 shows only one statistically significant difference between Second Career students and existing management. Second Career students tend to use the innovative RI strategic style less than does existing management.

Graphic 2

SECOND CAREER AND TRADITIONAL MASTER OF SCIENCE

STUDENTS vs. ESTABLISHED NURSING MANAGEMENT

SECOND CAREER AND TRADITIONAL MASTER OF SCIENCE

STUDENTS vs. ESTABLISHED NURSING MANAGEMENT

The difference in innovation based RI is large enough for both educators and employers to notice it. However, no single strategic style determines overall managerial “fit.” That requires considering all of a person’s strategic styles simultaneously.

To test the overall “fit” a composite profile was constructed by averaging the “I Opt” scores from all hospital management levels (from CNO to Assistant Nurse Manager). Student profiles falling within 30% of this standard were deemed to share management’s information processing perspective. They are likely to approach issues in about the same manner as existing management. Effectively, they can be seen as “management ready.”

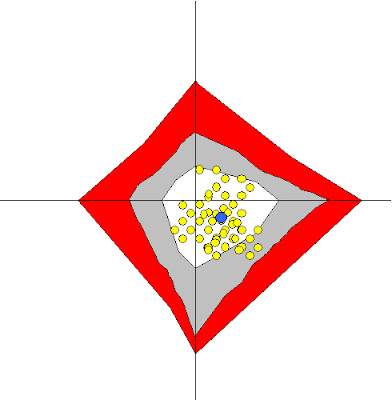

Graphic 3 shows the MS Program participants who lie within 30% of the management standard. The circles (i.e., centroids) are Cartesian averages. They locate a point of central tendency along all four of the “I Opt” styles simultaneously. Blue circles are the Second Career students, the yellow are the traditional. The red circle is the composite management centroid.

To test the overall “fit” a composite profile was constructed by averaging the “I Opt” scores from all hospital management levels (from CNO to Assistant Nurse Manager). Student profiles falling within 30% of this standard were deemed to share management’s information processing perspective. They are likely to approach issues in about the same manner as existing management. Effectively, they can be seen as “management ready.”

Graphic 3 shows the MS Program participants who lie within 30% of the management standard. The circles (i.e., centroids) are Cartesian averages. They locate a point of central tendency along all four of the “I Opt” styles simultaneously. Blue circles are the Second Career students, the yellow are the traditional. The red circle is the composite management centroid.

Graphic 3

SECOND CAREER AND TRADITIONAL

MASTER OF SCIENCE STUDENTS SCREENED

BY 30% MANAGERIAL CANDIDATE CONVENTION

The two types of MS programs appear to be functionally equivalent. Variation in some styles is compensated for by differences in others. The dispersion of both student groups is roughly equal.SECOND CAREER AND TRADITIONAL

MASTER OF SCIENCE STUDENTS SCREENED

BY 30% MANAGERIAL CANDIDATE CONVENTION

Table 1

PROPORTION MS STUDENTS WHO

DEVIATE 30% OR LESS FROM THE

EXISTING MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVE

Table 1 below reinforces equivalence. It shows that both programs are virtually identical in the depth of talent they provide. About 17% of the people in both programs have an “I Opt” profile that “fits” with the existing management. For managerial assessment purposes, the two programs can be treated as a single entity.

ADEQUACY OF THE “MANAGEMENT READY” NURSING POOL

Having two MS programs able to supply management talent is to be welcomed by the profession. However, the adequacy of the absolute size of the management pool merits investigation.

One method of testing adequacy is to compare nursing MS students with master degree candidates in other professions. A non-nursing average management standard was constructed using 4,945 executives from all industries and areas. The positions sampled were from General Manager through supervisor. The “I Opt” profiles of these executives were averaged to arrive at a non-nursing management standard.

A total of 611 masters’ candidates in disciplines such as engineering, business, computer science and manufacturing science from five universities provided a non-nursing sample. These students will typically fall under the supervision of the management identified as the standard. Students falling within a 30% range of the non-nursing “all management” standard are shown in Table 2.

The results are striking. Nursing has less than half of the depth of “management ready” masters’ candidates. One cause might be a difference in the standard being used. In other words, nursing might have a management standard (represented by the centroid of the average manager) more challenging than that of the other professions. Graphic 4 addresses this possibility.

PROPORTION MS STUDENTS WHO

DEVIATE 30% OR LESS FROM THE

EXISTING MANAGEMENT PERSPECTIVE

Table 1 below reinforces equivalence. It shows that both programs are virtually identical in the depth of talent they provide. About 17% of the people in both programs have an “I Opt” profile that “fits” with the existing management. For managerial assessment purposes, the two programs can be treated as a single entity.

ADEQUACY OF THE “MANAGEMENT READY” NURSING POOL

Having two MS programs able to supply management talent is to be welcomed by the profession. However, the adequacy of the absolute size of the management pool merits investigation.

One method of testing adequacy is to compare nursing MS students with master degree candidates in other professions. A non-nursing average management standard was constructed using 4,945 executives from all industries and areas. The positions sampled were from General Manager through supervisor. The “I Opt” profiles of these executives were averaged to arrive at a non-nursing management standard.

A total of 611 masters’ candidates in disciplines such as engineering, business, computer science and manufacturing science from five universities provided a non-nursing sample. These students will typically fall under the supervision of the management identified as the standard. Students falling within a 30% range of the non-nursing “all management” standard are shown in Table 2.

Table 2

NON-NURSING AND NURSING MASTERS CANDIDATES

SCREENED BY 30% MANAGERIAL CANDIDATE RULE

NON-NURSING AND NURSING MASTERS CANDIDATES

SCREENED BY 30% MANAGERIAL CANDIDATE RULE

The results are striking. Nursing has less than half of the depth of “management ready” masters’ candidates. One cause might be a difference in the standard being used. In other words, nursing might have a management standard (represented by the centroid of the average manager) more challenging than that of the other professions. Graphic 4 addresses this possibility.

Graphic 4

NURSE AND NON-NURSE ENTRY LEVEL SUPERVISORS INFORMATION PROCESSING PROFILES

Statistical tests confirm the obvious. There is no statistically significant difference between the two management groups. In information processing terms, nursing management could move to industry and nobody is likely to notice the difference—and vice versa

If the profiles of nurse/non-nurse management are the same and the methodology is the same, the character of people being attracted to nursing MS programs must be different. This is exactly the case. But the difference is not obvious. It requires the exact measurement capabilities of “I Opt” technology to lay the reason bear.

Graphic 5 shows that there are statistically significant differences between nursing and non-nursing masters’ candidates. The nurses are more idea-oriented (RI) and fall a bit short in their inclination toward analysis and assessment (HA). However the size of the differences do not appear to be enough to account for nursing having 50% fewer “management ready” candidates.

If averages cannot account for the divergence the answer must be in the distribution of students. This is exactly the case. Graphic 6 shows the centroid distribution of both nursing and non-nursing masters’ students. The non-nurse portion of the graphic uses a 110 person random sample drawn the 611-person non-nursing students. This makes the non-nursing group visually comparable to the 110 nurse MS population. There is no need to make mental adjustments for different size samples.

A quadrant by quadrant comparison reveals that the nurses are more widely scattered than their non-nursing counterparts. Nursing is apparently more hospitable to and thus attracts a wider range of perspectives than do other professions. The compassion that drives many nurses is more widely spread that are the mathematical capabilities of engineers or the logic of the computer scientists. This is as it should be in a healing profession.

IMPLICATIONS

Table 3 compares nurses in the MS programs with general staff nurses (including both graduate and non-graduate nurses).

NURSE AND NON-NURSE ENTRY LEVEL SUPERVISORS INFORMATION PROCESSING PROFILES

Statistical tests confirm the obvious. There is no statistically significant difference between the two management groups. In information processing terms, nursing management could move to industry and nobody is likely to notice the difference—and vice versa

If the profiles of nurse/non-nurse management are the same and the methodology is the same, the character of people being attracted to nursing MS programs must be different. This is exactly the case. But the difference is not obvious. It requires the exact measurement capabilities of “I Opt” technology to lay the reason bear.

Graphic 5 shows that there are statistically significant differences between nursing and non-nursing masters’ candidates. The nurses are more idea-oriented (RI) and fall a bit short in their inclination toward analysis and assessment (HA). However the size of the differences do not appear to be enough to account for nursing having 50% fewer “management ready” candidates.

Graphic 5

NURSE AND NON-NURSE

MASTER OF SCIENCE STUDENTS

NURSE AND NON-NURSE

MASTER OF SCIENCE STUDENTS

If averages cannot account for the divergence the answer must be in the distribution of students. This is exactly the case. Graphic 6 shows the centroid distribution of both nursing and non-nursing masters’ students. The non-nurse portion of the graphic uses a 110 person random sample drawn the 611-person non-nursing students. This makes the non-nursing group visually comparable to the 110 nurse MS population. There is no need to make mental adjustments for different size samples.

A quadrant by quadrant comparison reveals that the nurses are more widely scattered than their non-nursing counterparts. Nursing is apparently more hospitable to and thus attracts a wider range of perspectives than do other professions. The compassion that drives many nurses is more widely spread that are the mathematical capabilities of engineers or the logic of the computer scientists. This is as it should be in a healing profession.

Graphic 6

NURSE AND NON-NURSE MASTERS CANDIDATE

"MANAGEMENT READY" DISTRIBUTION

The effect of the dispersion of MS nurses is seen in the magnification. The circle in the center shows the number of people falling within 30% of the respective management standard (i.e., the green and red circles). Even though the sample size is the same, there are twice as many yellow circles among the non-nursing professions. The position of the management centroids differs slightly. But the wider ranging “I Opt” profiles among the nurses’ accounts for most of the dispersion.

NURSE AND NON-NURSE MASTERS CANDIDATE

"MANAGEMENT READY" DISTRIBUTION

The effect of the dispersion of MS nurses is seen in the magnification. The circle in the center shows the number of people falling within 30% of the respective management standard (i.e., the green and red circles). Even though the sample size is the same, there are twice as many yellow circles among the non-nursing professions. The position of the management centroids differs slightly. But the wider ranging “I Opt” profiles among the nurses’ accounts for most of the dispersion.

IMPLICATIONS

Table 3 compares nurses in the MS programs with general staff nurses (including both graduate and non-graduate nurses).

Table3

NURSING MS CANDIDATES Vs STAFF NURSES

SCREENED BY 30% MANAGERIAL CANDIDATE RULE

The MS offers a small increase in the pool of “management ready” talent. But the MS degree does not serve as a strong management filter. Since the nursing MS is targeted primarily at providing talent for the various nursing specialties, this is not an unexpected result.

However, nursing management is itself a specialty. Earlier studies (Staff Nursing Paradox and The Nurse Management Staircase) have shown that it demands a unique perspective. That perspective carries with it skills that are not widely shared. The exercise of these skills (or absence of them) effects such important areas as nurse retention, quality, efficiency and effectiveness. This is not a minor matter.

Simply attaching more standard “management” courses to the nursing curriculum is unlikely to have any effect in adding to the nurse management pool. Adding familiar course content focused on techniques, processes or organizational theory is unlikely to have an effect.

One reason is that the problem is not technical knowledge, it is in management perspective. Trying to address hospital level problems with the detailed orientation of a staff nurse is predestined to failure. Equally, trying to deal with the mechanics of a ward using the expansive hospital level thinking is likely to create a degree of very visible chaos. It does not matter how well the techniques used to apply these misaligned perspectives are executed.

Leadership training is also unlikely to remedy the condition identified here. The managerial perspective revealed by these nursing studies is not confined to leadership. It applies how problems are defined, the meaning of terms (e.g., “fast” means different things to different styles) and the “right” way to address an issue. All of these things and more are precedent to leadership. They define the direction that leadership will take. Adding skills on how to execute that direction will do nothing to address the fundamental issue of what that direction should be.

This research blog indicates that the dearth of management talent in nursing is going to persist. Nursing schools are unlikely to fill the gap. It is doubtful that students better aligned with a management perspective could be attracted in any appreciable numbers. A program to show nurses how to prepare themselves could help (see Migration Strategy below) but its effects in appreciably increasing the management talent pool will take many years to realize. Medical institutions will probably have to rely on themselves to grow the talent that they need.

THE MIGRATION STRATEGY

The interests of hospitals are probably best served by helping existing nurses who want to enter management to realize their aspirations. Standard management programs can teach them techniques and processes. What is needed is a method of aligning their information processing perspective with that of management. This does not happen automatically.

Unlike psychological states, “I Opt” information processing profiles can be changed. However, change cannot be imposed. This is because change is not confined to work. It affects an entire life and a personal commitment is needed to effect that kind of change. It is also not fast. Profile shifts typically take at least 18 months. A nursing management program aimed at aligning profiles will be neither inexpensive nor fast. But it can be done so that produces positive, cost reducing returns to the hospital along the way.

The basic idea is to provide the nurse candidate with specific tools to offset the vulnerabilities inherent in whatever profile that she holds. Then structure an environment so that she can use the tool repeatedly. As it is used, performance is improved. Another process then takes hold to yield lasting benefit to all involved. That process is that success breeds success.

The tool is merely a temporary aid. As it is used a nurse becomes increasingly familiar with the behavioral option it promotes. In practicing she is actually practicing the use of an alternative strategic style(s). With success the behavior becomes embedded in her repertoire of automatic responses—her strategic profile. Effectively, her profile is migrating from one state into another. This new state is preparing her to assume managerial responsibilities.

The migration strategy is a measured approach. There is no sudden shift in overall behavior. The nurse gets to work the new approach into her life pattern—at work, home and other venues in which she participates. Co-workers get the opportunity to adjust their expectations. The pressure on the nurse candidate to maintain past behavior patterns is reduced. The hospital gets steadily improving management performance.

Migration strategy process is simple. (1) Identify specific behavioral vulnerabilities using “I Opt” technology (2) design methods to offset them one at a time (3) practice (4) Once command is gained, return to item #1 for another vulnerability and restart the process. Since each nurse has a unique profile, the migration strategy is tailored to the specific needs of each nurse. The results can reasonably be expected to be more powerful than any “one size fits all” solution.

Space limitations prevent a fuller specification of the Migration Strategy here. An “I Opt” Engineering research blog Addendum is available for those interested in more detail

SUMMARY

This research has demonstrated that traditional and second career nursing MS programs are equivalent in their ability to produce managerial talent. Their common level exceeds that available from the general nursing staff but only by a small amount. Advanced nursing education does not appear to be geared to fill the nursing management gap.

The study also shows that the nursing Master’s program also falls far short of the results posted by other disciplines and areas. These other areas produce twice as many “management ready” graduates than does nursing. Evidence shows that this is not the result of the demands of nursing management. It is due to the nature of the nurses themselves.

This study traced the nurse management shortfall to the wide dispersion of “I Opt” profiles among nurses. This is likely that this is due to the nursing MS degree serving primarily as a tool for entering nursing specialty areas rather than as a vehicle for promotion to managerial ranks. This means that it is unlikely that traditional management development programs will address the issue identified. The issue lies at the very way the average nurse perceives the world, not how they go about executing a course though it.

Finally, an outline of a Migration Strategy for developing a managerial perspective was offered. It proposes a staged, systematic migration that will equip nurses to handle the kind of issues encountered at the various management levels. The process is outlined in this research blog and more fully specified in its Addendum.

NURSING MS CANDIDATES Vs STAFF NURSES

SCREENED BY 30% MANAGERIAL CANDIDATE RULE

The MS offers a small increase in the pool of “management ready” talent. But the MS degree does not serve as a strong management filter. Since the nursing MS is targeted primarily at providing talent for the various nursing specialties, this is not an unexpected result.

However, nursing management is itself a specialty. Earlier studies (Staff Nursing Paradox and The Nurse Management Staircase) have shown that it demands a unique perspective. That perspective carries with it skills that are not widely shared. The exercise of these skills (or absence of them) effects such important areas as nurse retention, quality, efficiency and effectiveness. This is not a minor matter.

Simply attaching more standard “management” courses to the nursing curriculum is unlikely to have any effect in adding to the nurse management pool. Adding familiar course content focused on techniques, processes or organizational theory is unlikely to have an effect.

One reason is that the problem is not technical knowledge, it is in management perspective. Trying to address hospital level problems with the detailed orientation of a staff nurse is predestined to failure. Equally, trying to deal with the mechanics of a ward using the expansive hospital level thinking is likely to create a degree of very visible chaos. It does not matter how well the techniques used to apply these misaligned perspectives are executed.

Leadership training is also unlikely to remedy the condition identified here. The managerial perspective revealed by these nursing studies is not confined to leadership. It applies how problems are defined, the meaning of terms (e.g., “fast” means different things to different styles) and the “right” way to address an issue. All of these things and more are precedent to leadership. They define the direction that leadership will take. Adding skills on how to execute that direction will do nothing to address the fundamental issue of what that direction should be.

This research blog indicates that the dearth of management talent in nursing is going to persist. Nursing schools are unlikely to fill the gap. It is doubtful that students better aligned with a management perspective could be attracted in any appreciable numbers. A program to show nurses how to prepare themselves could help (see Migration Strategy below) but its effects in appreciably increasing the management talent pool will take many years to realize. Medical institutions will probably have to rely on themselves to grow the talent that they need.

THE MIGRATION STRATEGY

The interests of hospitals are probably best served by helping existing nurses who want to enter management to realize their aspirations. Standard management programs can teach them techniques and processes. What is needed is a method of aligning their information processing perspective with that of management. This does not happen automatically.

Unlike psychological states, “I Opt” information processing profiles can be changed. However, change cannot be imposed. This is because change is not confined to work. It affects an entire life and a personal commitment is needed to effect that kind of change. It is also not fast. Profile shifts typically take at least 18 months. A nursing management program aimed at aligning profiles will be neither inexpensive nor fast. But it can be done so that produces positive, cost reducing returns to the hospital along the way.

The basic idea is to provide the nurse candidate with specific tools to offset the vulnerabilities inherent in whatever profile that she holds. Then structure an environment so that she can use the tool repeatedly. As it is used, performance is improved. Another process then takes hold to yield lasting benefit to all involved. That process is that success breeds success.

The tool is merely a temporary aid. As it is used a nurse becomes increasingly familiar with the behavioral option it promotes. In practicing she is actually practicing the use of an alternative strategic style(s). With success the behavior becomes embedded in her repertoire of automatic responses—her strategic profile. Effectively, her profile is migrating from one state into another. This new state is preparing her to assume managerial responsibilities.

The migration strategy is a measured approach. There is no sudden shift in overall behavior. The nurse gets to work the new approach into her life pattern—at work, home and other venues in which she participates. Co-workers get the opportunity to adjust their expectations. The pressure on the nurse candidate to maintain past behavior patterns is reduced. The hospital gets steadily improving management performance.

Migration strategy process is simple. (1) Identify specific behavioral vulnerabilities using “I Opt” technology (2) design methods to offset them one at a time (3) practice (4) Once command is gained, return to item #1 for another vulnerability and restart the process. Since each nurse has a unique profile, the migration strategy is tailored to the specific needs of each nurse. The results can reasonably be expected to be more powerful than any “one size fits all” solution.

Space limitations prevent a fuller specification of the Migration Strategy here. An “I Opt” Engineering research blog Addendum is available for those interested in more detail

SUMMARY

This research has demonstrated that traditional and second career nursing MS programs are equivalent in their ability to produce managerial talent. Their common level exceeds that available from the general nursing staff but only by a small amount. Advanced nursing education does not appear to be geared to fill the nursing management gap.

The study also shows that the nursing Master’s program also falls far short of the results posted by other disciplines and areas. These other areas produce twice as many “management ready” graduates than does nursing. Evidence shows that this is not the result of the demands of nursing management. It is due to the nature of the nurses themselves.

This study traced the nurse management shortfall to the wide dispersion of “I Opt” profiles among nurses. This is likely that this is due to the nursing MS degree serving primarily as a tool for entering nursing specialty areas rather than as a vehicle for promotion to managerial ranks. This means that it is unlikely that traditional management development programs will address the issue identified. The issue lies at the very way the average nurse perceives the world, not how they go about executing a course though it.

Finally, an outline of a Migration Strategy for developing a managerial perspective was offered. It proposes a staged, systematic migration that will equip nurses to handle the kind of issues encountered at the various management levels. The process is outlined in this research blog and more fully specified in its Addendum.