Chief: Research & Development

Professional Communications, Inc.

INTRODUCTION

This evidence-based research blog outlines the discovery of a nursing staircase. Its steps are systematic and quantifiable. The staircase impacts patient care, nursing quality, organizational effectiveness and nurse retention among many other things.

The staircase automatically creates a communication “gap.” This can compromise coordination and can give rise to significant tensions that can affect an entire nursing organization. This research shows the dimensions of the issue and traces some of its implications as applied to nursing.

NURSING MANAGEMENT

This study draws on data from two hospitals. One is a government facility and the other a private hospital. A total of 52 nurses in management positions guide the activities of 344 staff nurses.

As with other goal directed organizations, nursing management is a hierarchy. In this study the Chief Nursing Executive and various Nurse Administrators (e.g., Cardiac, Woman's Health, etc.) occupy senior positions. The Nurse Manager sits in the middle and the Assistant Nursing Manager lies at ranks below. The hierarchical composition and names assigned vary by hospital but there are always positions at the different levels.

Graphic 1 shows that the information-processing strategies used by these various levels at the hospitals studied differ both systematically and significantly.

Graphic 1

INFORMATION PROCESSING STRATEGIES

OF LEVELS OF NURSING MANAGEMENT

INFORMATION PROCESSING STRATEGIES

OF LEVELS OF NURSING MANAGEMENT

A “stair step” arrangement of information processing strategies is instantly apparent. The higher the level, the less reliance is placed on structured approaches (LP and HA) and the greater the dependence on strategies that build on unpatterned input (RS and RI). This is same phenomena has been found in non-nursing teams, in functional areas such as engineering and in hierarchies in general. As yet unpublished ongoing research has revealed many similar instances. The relationship is ubiquitous.

THE STAFF NURSE

The “stair step” relationship within the management structure creates issues between management levels. However, the real impact on any organization will be felt where “the rubber hits the road.” In the case of nursing, that happens at the staff nurse level.

The staff nurse is the core of any hospital. They are the people who nursing management must successfully direct in order to realize their vision. A companion Staff Nursing Paradox research blog has shown that staff nurses tend to use a Logical Processor (LP) strategic style. This earlier study argues that the LP style is the one best suited to their core function. Graphic 2 reveals that the staff nurse’s choice fits neatly into the “stair step” found in management. Exactly the same managerial “gap” processes are at work throughout the hierarchy.

Graphic 2

INFORMATION PROCESSING STRATEGIES

INCLUDING STAFF NURSES (in red)

INFORMATION PROCESSING STRATEGIES

INCLUDING STAFF NURSES (in red)

The fact that the differences are significant is apparent from Graphic 2. However, just to be sure the various management levels were consolidated (n=52) and compared to the staff nurse population (n=344). In every case the level of statistical significance far exceeds academic standards at the p < .001 level. This is no accidental relationship.

The fact that the differences are significant is apparent from Graphic 2. However, just to be sure the various management levels were consolidated (n=52) and compared to the staff nurse population (n=344). In every case the level of statistical significance far exceeds academic standards at the p < .001 level. This is no accidental relationship. IMPLICATIONS

There is no mystery on why the staircase has evolved. As a person rises in a hierarchy the problems they address become less and less “standard.” Issues that can be resolved by traditional practices (LP-action based) and by known analytical processes (HA-thought based) have been already addressed at lower levels. The manager is left with issues that favor innovative approaches (RI-thought based) and/or which require decisive action even in the absence of full information (RS-action based).

The staircase is the result of a natural filter. It systematically sorts out people by their information processing approach. It matches these to the kinds of issues that exist at the various organizational levels. But there is also a cost. The “stair steps” are communication impediments. In order to address an issue at a particular level, you have to focus on it. In doing that, you lose focus on allied issues at other levels.

For example, a nurse facing a patient related crisis is likely to instantly deploy methods she knows work in a manner that has proven to be efficient and effective (an LP approach). In doing this she automatically loses focus on the possibility of less certain but potentially more viable options that might be applied (the RI approach). If these kinds of issues continually arise, the strategic style tends to be reused. With reuse the approach solidifies into a perspective. It becomes an efficient and effective way of navigating life.

People whose “I Opt” strategic profile (i.e., the combination of styles they normally employ) match the demands of a particular environment tend to prosper. They begin to generalize their strategies. If it works here, it must work there. Their strategy becomes the “right” way to do things. People addressing these issues using a different strategy are “wrong.” After all, if there is a “right” there must be a “wrong.” Thus is born a basis for organizational tension.

This kind of thinking can even leak into the meaning of words. For example, a person working in a Trauma Center is likely to favor the instant action RS style. That person will probably interpret the word “fast” to mean immediately. The RS interpretation works in the Trauma environment. This is evidence that it is the “right” meaning.

A person working in Radiology will probably favor the analytical HA style. They are likely to see “fast” as meaning as soon as things have been completely thought out. As with the RS above, this meaning of fast becomes generalized. Same word, different meanings.

The example used the word fast. In fact any term that is relative in nature is subject to this kind of interpretation divergence. For example terms like creative, thorough and precise are equally susceptible. This alone is enough to cause serious coordination problems. But it does not stop there.

The meaning of words sets expectations. Expectations are the standard against which judgments of “good” or “bad” are made. When applied to work performance these judgements of good and bad can influence assignments, raises and promotions. This is serious business.

People compare their judgment of what they have done with that of the person evaluating them. If these two people have different strategic profiles (i.e., different information processing strategies) the standards used can vary. One person can see an assessment as "just" while the other believes they have been “wronged.” At this point emotions can come into play. A different standard backed by emotional energy is a formula for continuing tension.

There is no right or wrong here. Both parties in the example are using a “right” strategic posture. Both parties have interpreted the terms being used in a “right” way. The standards based on their “right” interpretations are themselves “right.” What has happened is that the staircase has built divergence into the system. The divergence cannot be avoided. It can only be managed.

STAIRCASE MANAGEMENT

The existence of the staircase presents chronic but not fatal problems. The structure has functioned for centuries in various forms and can probably continue to function for centuries more. Prior to “I Opt” uncovering its basic dynamics, there was not much to be done. Now there is.

Minimizing misinterpretation and its associated standards divergence is simple. Just make sure everyone knows where everyone else is “coming from.” This transparency only requires access to “I Opt” profiles. There is nothing secret about them. We all display them every day. The problem is that not everyone sees each other every day. That means that it is easy to make a wrong guess just because of selective, irregular exposure.

The benign character of “I Opt” profiles has been demonstrated. "I Opt" has multiple major clients (i.e., Fortune 500 firms) who regularly use small foam profiles mounted for display. They are passed out in training and consulting sessions. They end up on display in offices and workstations and can stay there for years. Some clients have been using this tool for a decade. If there were any exposure they would have discovered it by now. No problem has ever arisen.

Even smaller steps can help. Individual “I Opt” profiles evolve to fit the specific life that is being led. We did not “choose” them. People see these patterns in their own behavior. People will refer to themselves as creative, precise, analytically adept or responsive. But they seldom reflect on the implications of these patterns. The “I Opt” profile makes these implications visible. Visibility quickly converts to knowledge. Knowledge is a precondition for the adjustment mechanisms that limit misinterpretation. It is a good thing.

Transparency comes with a bonus. It limits emotional escalation. For humans, behaviors always have a “reason.” If one is not apparent, it is created. An easy attribution for offensive behavior is malicious intent. With this can come an enduring emotional response. This is a bad thing.

The availability of an alternative “reason” reduces the likelihood of assigning malicious intent as a cause. The “I Opt” profile provides that alternative. The behavior might still be offensive but at least does not carry the same intentional component. The chances emotional escalation are reduced.

STAIRCASE EFFICIENCY AND EFFECTIVENESS

The staircase works by Darwinian selection. People are selected and installed in management positions. Over time they either work out or don’t. If they don’t workout they either separate themselves or are otherwise separated. The people who remain generally fit the needs of the role.

The first option for improving staircase operation fits into the earlier transparency prescription. “I Opt” styles are not immutable. They can be changed. Telling nurses how they might fit into the staircase can be a first step. A report that identifies their strengths and exposures in a leadership context can give them a template. If the fit is not good for a position to which they aspire they can start making adjustments. Change is not easy but it can be done.

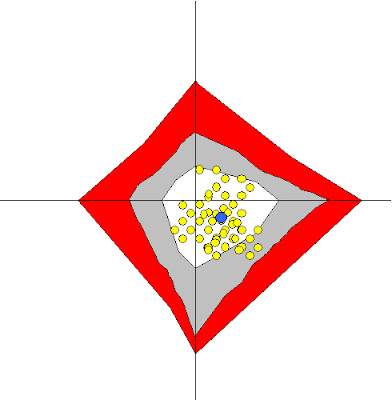

Another option is to use the “I Opt” profile as a scanning mechanism. For example, Graphic 3 shows the results of scanning the 344 staff nurses in this study against the average profile of an Assistant Nurse Manager. The circle designators (i.e., centroids) are Cartesian Averages that locate the point of central tendency along all four of the “I Opt” styles simultaneously. Yellow circles identify nurses falling within 30% of the Assistant Nurse Manager (in blue). The scan isolates those nurses whose strategic style perspective roughly matches that of presumably successful existing management.

Graphic 3

SCAN OF NURSES WITHIN 30% OF

ASSISTANT NURSE MANAGER PROFILE (in blue)

SCAN OF NURSES WITHIN 30% OF

ASSISTANT NURSE MANAGER PROFILE (in blue)

The scan cannot be used as a selection mechanism. It does not consider things like experience, education, aptitude or any number of other factors that are relevant to selection. But it can serve to alert management to potential candidates who might otherwise have been missed. For example, a nurse working the night shift may not get the exposure of an equivalent person working the day shift. A scan can help level the playing field.

The screening standard in the example was the Assistant Nurse Manager. There is some indication that various parts of the hospital favor somewhat different profiles. Graphic 4 contrasts nurse managers from the ICU and Trauma Center.

Graphic 4

ICU vs PSYCH MANAGERS AVERAGE

STRATEGIC STYLE DISTRIBUTION

ICU vs PSYCH MANAGERS AVERAGE

STRATEGIC STYLE DISTRIBUTION

The sample is admittedly thin. But it serves to alert the nurse leader to the fact that the standard used for scanning can be tailored to specific needs. All that needs happen is to adjust the average used as a standard. People at relevant level of management in the area of interest can serve as a standard just as well as did the Assistant Nurse Manger in the example used here.

The sample is admittedly thin. But it serves to alert the nurse leader to the fact that the standard used for scanning can be tailored to specific needs. All that needs happen is to adjust the average used as a standard. People at relevant level of management in the area of interest can serve as a standard just as well as did the Assistant Nurse Manger in the example used here.Darwinian processes will eventually sort out the well suited and ill suited to create the staircase. However, the process is inefficient and unnecessarily brutal. Scanning the pool of possibilities can help insure that people who already have appropriate perspective are considered. People whose strategic profile is ill suited but who are otherwise qualified can be given support to increase their odds of success. It is a win-win for all involved—the hospital and the candidates.

SUMMARY

Information processing profiles form a staircase. The staircase was not planned. It is the outcome of a natural filtering process that aligns an individual’s information processing strategy with the nature of the work being performed. It will always be there.

It is the staircase that integrates the patient, ward/unit and hospital level interests into a single, unified whole. All of the different information flows, distinct objectives and unique responses are accommodated somewhere on the staircase. The staircase is what allows a hospital—along with all of the benefits it provides—to exist.

The staircase carries some inherent downside aspects. Miscommunication along with its potential for emotional escalation is one of the more ubiquitous exposures. This cannot be escaped but it can be minimized. The simplest, least expensive and most durable way of doing this is a program of transparency.

The staircase is constantly being rebuilt as new people come and go. The Darwinian process that produces the staircase can be refined. The populations of potential management candidates can be scanned to insure that everyone who merits consideration is in fact considered. People whose skills match the hospitals needs but whose information processing perspective is misaligned can be helped to adjust.

Nothing will dissolve the issues that the staircase creates. However, knowledge that the staircase exists and awareness of the processes that produce it give nurse management an edge. They can now actively manage the process. In doing so the entire nursing profession will be well served. Hospital management becomes more efficient and effective. Professional nurses will work in a more supportive environment and are given a “fair shot” at management positions regardless of where or when they work. The information processing perspective is a concept worth incorporating in the toolbox of the nursing profession.